The models are wrong, climate change is accelerating faster than predicted

↵

Scientists are starting to realise that the climate models they have been using to predict the rate of global warming are wrong as it becomes clear temperatures are rising faster than predicted.

The world has just registered its hottest year on record, hotter than expected by the climate models, and as a heatwave sweeps the world this spring coupled with sea temperatures already smashing all-time highs set only last year, it appears this year is going to be even worse than last year, Berkely Earth reports in its temperature tracker.

That is a big problem, as these models have been the basis of action to combat climate change in the 2015 Paris Accords. Governments have been failing to meet the Paris targets, but it was thought that there was still time to make a difference. But if the models are wrong and underestimating the pace of climate change, it may be that it is already too late to prevent a climate catastrophe. Certainly, the academic papers covering climate change are already starting to sound more shrill in their reporting on the trends and begun to call global warming an “existential challenge.”

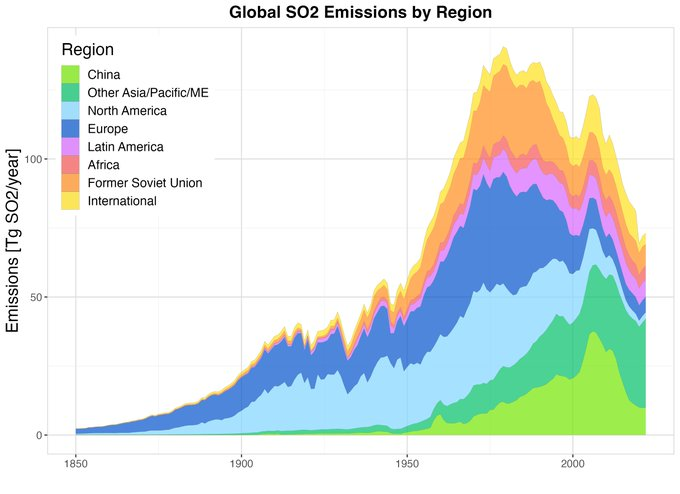

The problem appears to be that while the climate models accurately account for the effects greenhouse gases (GHGs) have on the weather systems, the academics didn’t take into account the effect taking sulphur dioxide out of ship fuel is having.

A global campaign to remove SO2 from ship exhaust was launched in 2020 and has been very successful. SO2 is a GHG, but its side effect was that once in the atmosphere it also very effectively reflects sunlight back into space, cooling the planet. Once the SO2 was removed, more sunlight is reaching the planet’s surface, and net-net is increasingly the temperature more than removing SO2 as a GHG is cooling it.

SO2 emissions by region over time

“When it comes to climate risk, aerosols are wickedly more complicated than are greenhouse gases,” according to a recent paper in Nature, “Aerosols must be included in climate risk assessments,” by Geeta G. Persad et al.

“The silence on aerosols that we set out here has become self-fulfilling. Because the current toolkit is largely blind to this climate risk, much of the community has come to view aerosols as largely unimportant. This has limited the sophistication, realism and range of risk modelling that is ‘aerosol aware’,” Persad wrote.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report, that was prepared for COP28 and is the current touchstone of climate change results, relies mainly on the pattern of climate effects from warming driven by greenhouse gases (GHGs) when quantifying “climate impact drivers”.

“All of these models are only as good as the data they ingest. The aerosol-emission inventories that are fed into Earth system models are often coarse in space and time, creating uncertainty. In fact, a 2021 study showed that the version of this inventory that was used for the latest IPCC report markedly underestimates trends in aerosol emissions in China over the past 5-10 years (and, consequently, whether recent changes in these aerosols are causing cooling or warming),” says Persad.

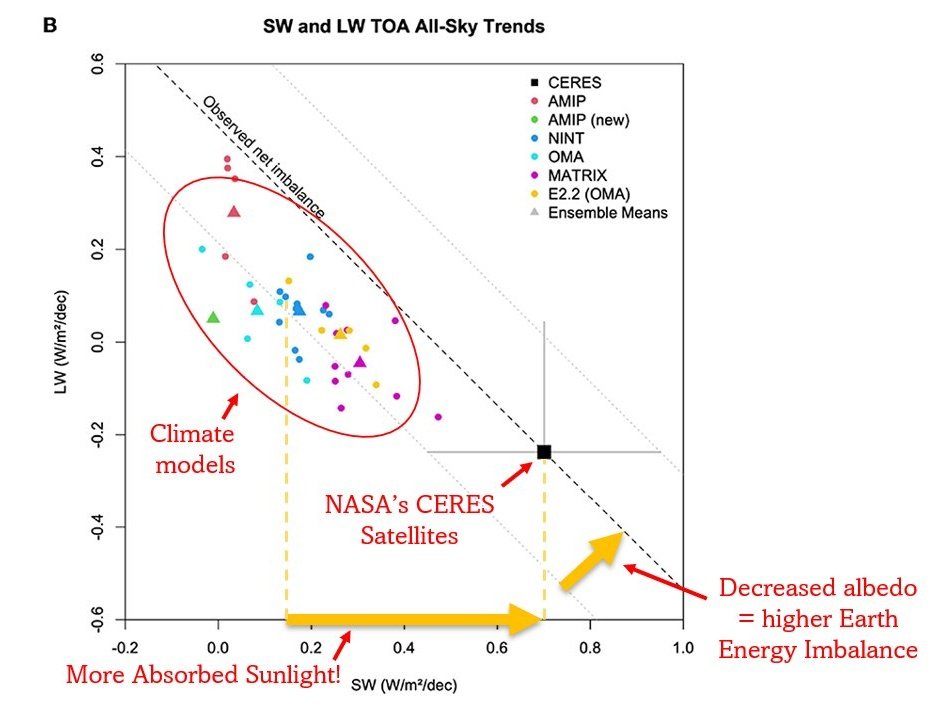

In scientific terms aerosols affect the Earth Energy Imbalance (EEI) is rising and the EEI effect was not included in the climatic models. The problem with sunlight – a new vector on calculating global warming – is made worse by the current solar cycle, called Cycle 25, that is irradiating the earth with more heat than normal, which is expected to peak this year or next. Neither of these effects are included in the current climate models and should be.

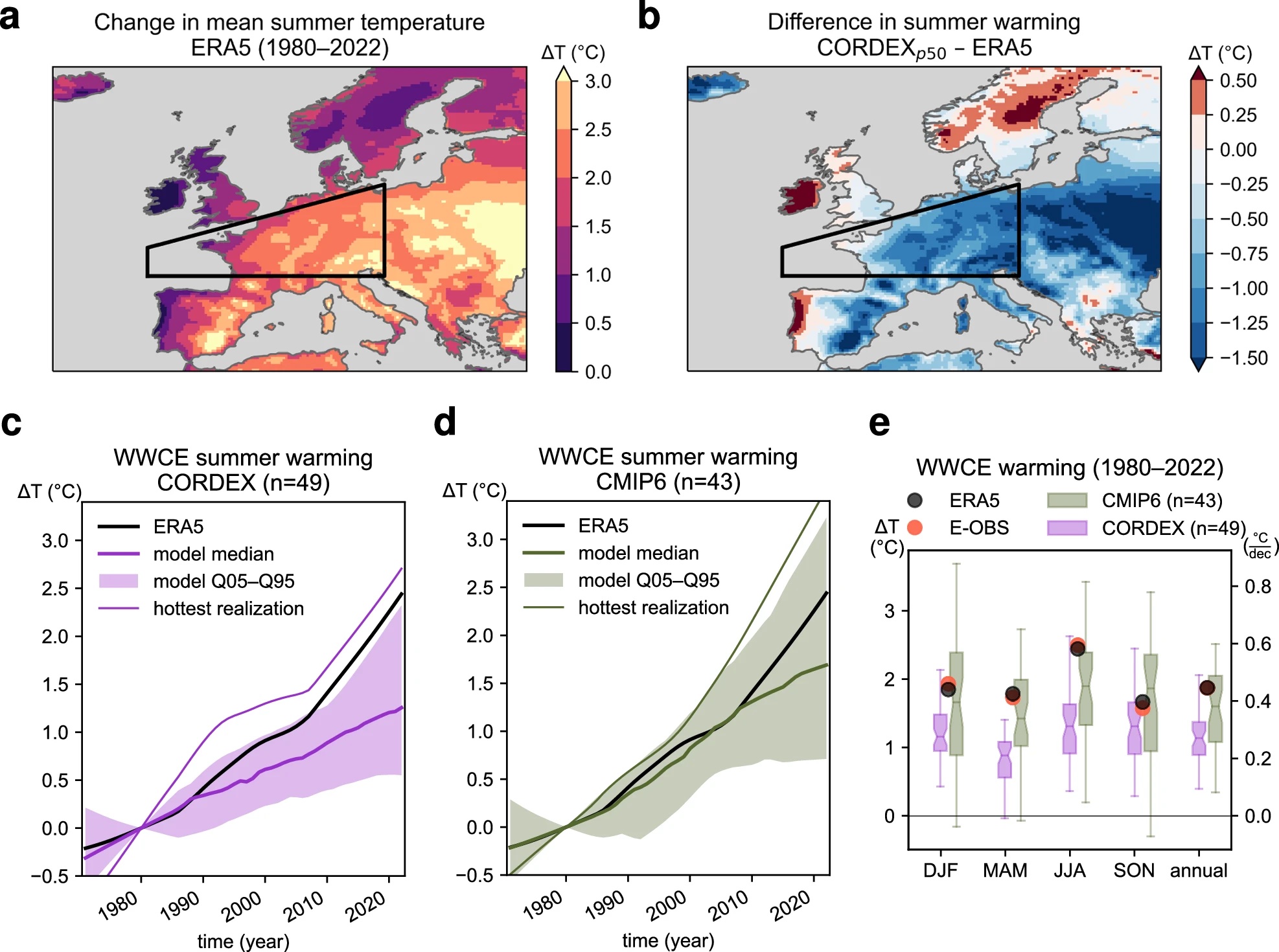

“The models don't take into account the reduction of aerosols over western-central Europe and underestimate regional warming by ~0.5C!! And summer warming by ~1.0C!,” climatologist Lee Simmons said in a recent post.

All the climate models have underestimated the observed increases in temperatures in recent years

Acceleration

The EEI effect is being seen around the world. Europe has warmed faster than any other region since the 1980s, with annual mean temperatures increasing twice as much as the global average. This is even more pronounced in Western Europe, where temperatures are increasing nearly three times faster than the global average (~2.3 °C compared to ~0.8 °C).

Russia’s Arctic regions were warming twice as fast as the rest of the world a few years ago, as the poles tend to warm faster than the equator, but that rate has risen to seven times as fast last year, according to recent Russian meteorological research.

In general, 20 out of 35 environmental vital signs that climatologists used to track the state of play have crossed their upper safe bounds limits sooner than predicted. Everywhere you look, new records are being shattered and during this spring in some regions in Africa and Asia in particular, they are being broken on a daily basis.

In the latest disaster, scientists have been reporting that 80% of the earth’s coral is already dead or dying due to the abnormally high sea temperatures.

"It’s not like we’re breaking records by a little bit now and then. It’s like the whole climate just fast-forwarded by fifty or a hundred years,” says Brian McNoldy, senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School, told the New Yorker in a recent interview.

The climate models that are excluding the effect of removing sulphur dioxides are badly underestimating the rate the world is warming. Negative effects that were not expected to manifest themselves for hundreds of years are already becoming visible.

The North Atlantic Ocean was a particular area of concern, with temperatures there described as bathwater. The temperature readings in this basin were "off the charts” at the start of this year, according to Copernicus, a branch of the European Union's space programme, in a significant deviation from the norm.

The hotter than it should be Atlantic is threatening to cause the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) to collapse at some point, a current that brings warm water from the equator to the north. As bne IntelliNews reported, if that happens it could lead to a mini-ice age in Northern Europe, where winter temperatures could fall by as much as 30C.

The unusual heat in the sea was not predicted by scientists, even allowing for last year’s El Niño effect, and has led to them to ask if some other factor is at work, causing warming to accelerate. Increasingly they are concluding the answer is yes. The models are wrong. Things are worse than they seem.

“We don’t really know what’s going on,” Gavin Schmidt, the director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, told the New Yorker. “And we haven’t really known what’s going on since about March of last year.”

Scientists are going back to the drawing board as more data comes in and allows them to test their models. Last summer’s record-breaking temperatures has set alarm bells ringing as the models were badly off.

“In much of western-central Europe, summer temperatures have surged three times faster than the global mean warming since 1980, yet this is not captured by most climate model simulations,” Schumacher, D.L., Singh, J., Hauser, M. et al. said in a paper entitled Exacerbated summer European warming not captured by climate models neglecting long-term aerosol changes, published this month in Communications Earth & Environment.

The team concluded that failing to include the EEI effect from removing aerosols from the air has had a huge effect and recommend that the entire climate model regime that governments have been basing their decisions on needs to be completely overhauled.

The study went on to compare the median temperature predicted by a few of the leading models (there are more than 30 respected models in use by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) showed the actual temperatures were a lot more than the model’s median prediction and indeed above even their most extreme upper bands.

Europe reassess

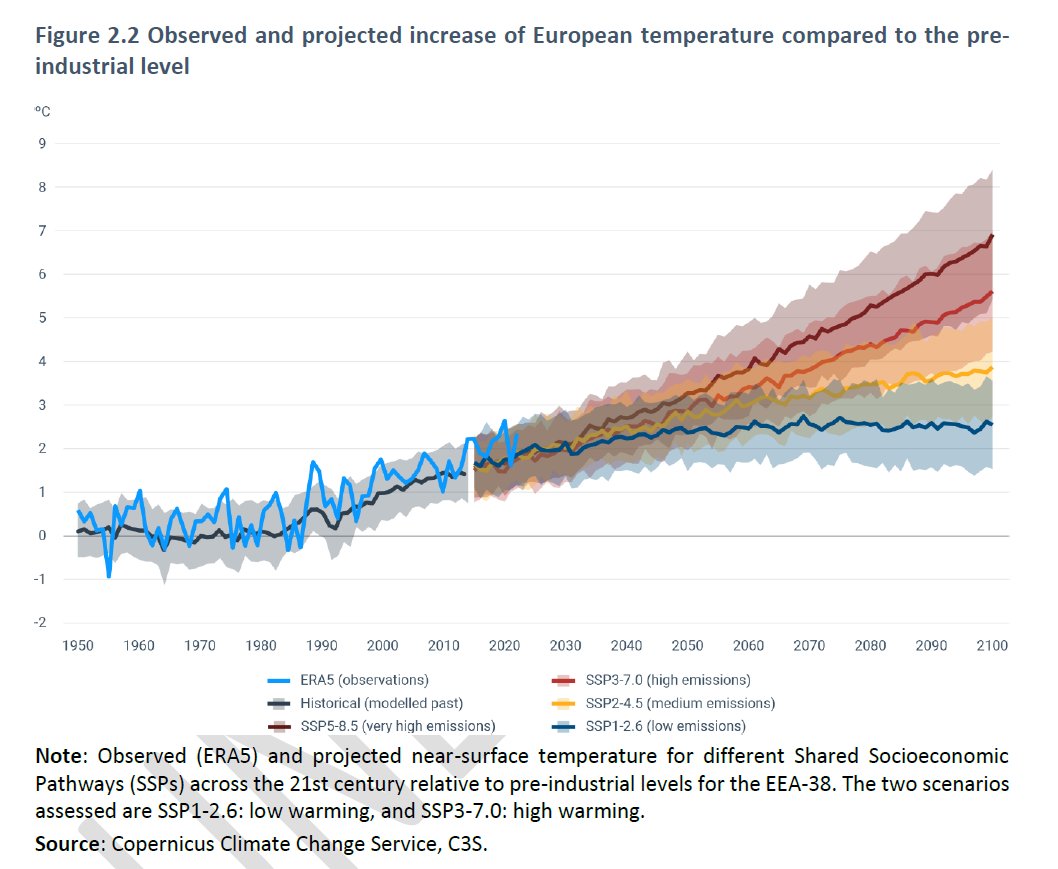

The European Environment Agency (EEA) also released is first ever climate impact report in April that also warned climatic models have been underestimating the pace of warming and making some dire predictions.

The observed rate of increase of annual mean temperature for specific regions in Europe is more than 2.5 times the global mean temperature increase.

In one chart that extrapolates temperature increase in Europe predicts temperatures might rise by as much as 7C by 2100 and that holding the increase to 2C, the stated upper goal, is the least likely scenario.

"Population exposure to extreme heat is projected to increase to 172mn per year by 2100 under a low-emissions scenario and to nearly 300mn/year under a high-emissions scenario,” the report warns.

Europe’s temperatures will rise by at least 2C and could rise 7C in the coming 80 years

As an aside, the report is also predicting increased health risks are already appearing as a result of temperature increases already seen: "Mosquito- and tick-borne diseases that have either expanded their range or recently emerged in the EU include: West Nile virus, chikungunya, dengue, Lyme disease, tick-borne encephalitis and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever… Biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation is a major environmental threat in Europe, and it is accelerating."

As the pace of heating picks up, water and agriculture is going to come under increasing pressure.

"Increasing frequency and severity of low flows will lead to hydrological droughts and worsening water scarcity in southern and western-central Europe, the EEA says. "Food production is at risk from reduced water availability and quality as well as the deteriorated status of terrestrial and marine ecosystems."

The academic research is becoming uncharacteristically shrill in its warnings. A regular update on the climate changes in 2023 published by Oxford Academic was entitled “Entering Uncharted territory” and warned most of the climate benchmarks have moved into the flashing red warnings zones.

"Life on planet Earth is under siege. We are now in an uncharted territory. For several decades, scientists have consistently warned of a future marked by extreme climatic conditions because of escalating global temperatures caused by ongoing human activities that release harmful greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. Unfortunately, time is up,” William Ripple et al said in a paper in December.

The team reported that the worst-case scenarios are being manifest “as an alarming and unprecedented succession of climate records are broken, causing profoundly distressing scenes of suffering to unfold. We are entering an unfamiliar domain regarding our climate crisis, a situation no one has ever witnessed firsthand in the history of humanity.”

The paper goes on to detail that 20 of the 35 planetary vital signs” are now showing record extremes. The data shows how the continued pursuit of “business as usual” has, ironically, led to unprecedented pressure on the Earth system, resulting in many climate-related variables entering “uncharted territory.”

Moreover, after a brief respite during the coronavirus pandemic, the three important GHGs – carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide – all reached record levels in 2023. Moreover, the global average carbon dioxide concentration is now approximately 420 parts per million, which is far above the proposed planetary boundary of 350 parts per million.

And like the other researchers, the Oxford team also point to “a global decline in sulphur dioxide emissions as likely a contributing factor.”

“The effects of global warming are progressively more severe, and possibilities such as a worldwide societal breakdown are feasible and dangerously underexplored,” the Oxford paper says. “By the end of this century, an estimated 3bn to 6bn individuals – approximately one-third to one-half of the global population – might find themselves confined beyond the liveable region, encountering severe heat, limited food availability, and elevated mortality rates because of the effects of climate change. Big problems need big solutions. Therefore, we must shift our perspective on the climate emergency from being just an isolated environmental issue to a systemic, existential threat.”

Follow us online